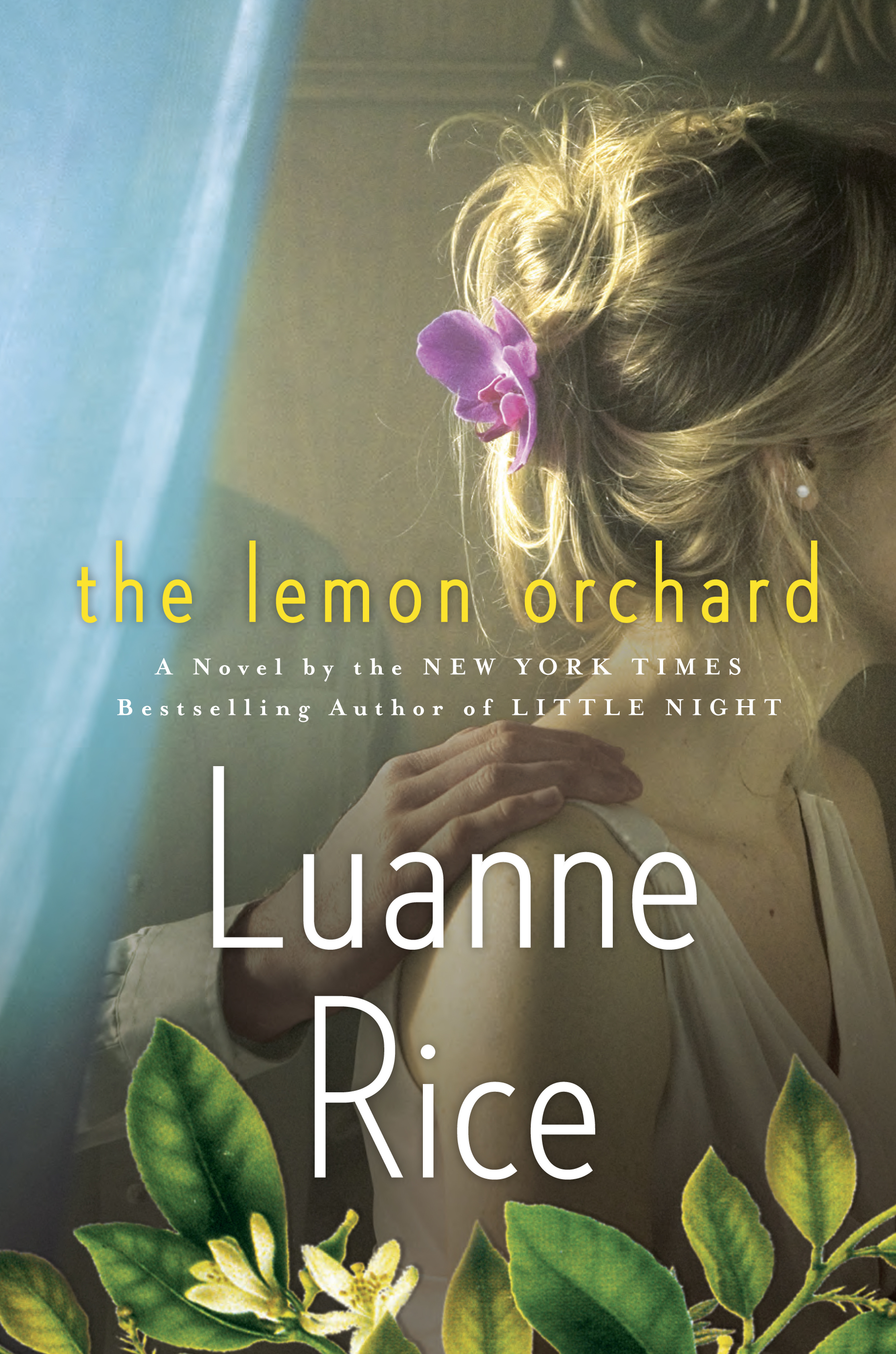

I'm thrilled to be able to share with you the prologue from my new book, Little Night.

February 14, 1993

My hands are bandaged, but I’m not supposed to care that they hurt. When I was treated at the scene, the husky EMT said flatly, “He’s a lot worse off than you.” The police officer had to remove my handcuffs; he snapped on latex gloves to avoid having to touch my burned palms and wrists.

They drove me in a squad car to the East Hampton station house for booking, and finally into the sheriff’s van for the ride here to the county jail, fifteen miles away in Mashomuck.

I’ll tell you one detail because it’s frozen in my mind. The phrase “two to the head.” That’s what I’ve been hearing since the police arrived. “She gave him two to the head.” Then they laugh at me. It’s supposed to be a big joke about how inept I was.

This enormous, shaved-head bodybuilding sheriff acted it out for me in the van on the way here. “One,” he said, pretending to clobber the other sheriff over the head. “Two.” He imitated the second blow. Then, “Ouch,” he said as he waggled his fingers at me and winked nastily at my bandaged hands. “You burned yourself as bad as you hurt him, but he’s going to the hospital and you’re going to jail.”

I’d like to block his words out. They make this seem like any other crime, one of the salacious stories you see on CNN Headline news. To the outside I suppose all crimes are the same—someone attacks, another is injured. It’s only in a person’s mind and heart, only within the soul of any given family that the entire tender, brutal, surreal story makes any sense.

I say “family,” but it might only be me. I have three blood relatives in this world: Anne, my older and only sister, and her children, a niece and nephew I barely know because her husband has cut us off so thoroughly. Blood is one thing, but to be family, you need so much more.

This morning I’d reached my breaking point on that and taken the LIRR out east, unannounced, to show up with roses for Anne and books and Valentines for the kids. I chose late morning, when Frederik would be at his gallery. The day was bright blue but frigid, no humidity, a sharp wind whirling around Montauk Point.

I caught a cab from the station to their house on Old Montauk Highway. I was a wreck, thinking she’d slam the door in my face. But she didn’t—she let me in. Right now I can hardly stand the memory of seeing the shock and joy in her eyes, feeling our strong embrace, as if our lives in that instant had been reset, back to the time before him.

The children didn’t know who I was. They’re only three and five, and I last saw them all at my mother’s funeral a year ago, when Frederik had dragged the family away from the gravesite before Anne and I had a chance to console each other, or even speak.

For twenty minutes today we had a good time. The house was freezing; obviously the heat was turned way down. Anne, Gillis (“Gilly”), and Margarita (“Grit”) wore warm shirts and fleece pullovers. I kept my jacket on. We huddled around the hearth where two logs sparked with a dull glow; a third had barely caught, flames just licking the top edge.

The brass screen had been set aside, as if to keep the wire mesh from holding back the fading warmth. I glanced around for a poker, but saw nothing to stoke the fire. There didn’t seem to be any more wood either.

I was afraid to ask about the heat, or lack of it. Anything can trigger Anne, especially when it comes to Frederik. She might have taken my question as implied criticism of his ability or willingness to provide basic needs for his family. She’s very defensive about him. But the truth is, she’s always had a strange, secret side when it came to men. She puts them on pedestals, and then subverts them in ways they’d never guess.

I’ll confess something else: Anne and I had probably been the closest sisters on earth, but we have never been completely, one-hundred-percent easy with each other. I don’t believe Anne can be that way with anyone.

While we sat and talked today, she was old Anne, and it felt as if she’d spent the last five years waiting for my visit.

The children seemed numb at first. They smelled the pearl-white roses I’d brought, and touched the Valentine cards and books, and looked up at me as if they weren’t sure whether they should smile or not. I’d brought my camera, and I took a picture. Their hesitant smiles killed me.

“Who is she?” Gilly whispered to Anne.

“She’s your aunt,” Anne said.

He stared, as if he’d never heard the word before.

“I’m your mother’s sister,” I said.

“Mommy doesn’t have a sister,” Gilly said.

“I do,” Anne said. “Just like you do.”

She squeezed my hand so they would see. Grit broke into a smile.

I asked if they drew pictures, and they both ran to get their drawings. Soon we were coloring together, and Anne seemed happy and almost relaxed, and except for the cold, everything was all right.

I hadn’t been to the house in five years, since right after Anne married Frederik. They’d invited my mother, Paul, and me to their Jul party. That night of the party is stamped in my mind. Climbing out of the car, I had my first look at their formidable glass house on the lighthouse road, surrounded by acres of scrub pines and thick brambles, an incredible habitat for birds. We rang the doorbell, and Frederik answered.

He kissed my mother and me, once on each cheek, and shook my fiancé, Paul Traynor’s, hand. He took our coats, gestured around the majestic, cathedral-ceilinged room. “I’m king of all I survey,” Frederik said in his elegant Danish accent. “And now Anne is queen.”

“King Frederik and Queen Anne!” I said.

Frederik didn’t smile, and he backed away. “Please enjoy my glasswork and help yourself to glogg and the buffet. I must find Anne and tell her you are here.”

“That was weird,” I said to my mother and Paul. “Did I do something wrong?”

“No,” Mom said. “Maybe the humor got lost in translation.”

“Maybe it’s not a joke and he really thinks he’s king. He’s definitely an over-shaker,” Paul said, flexing his hand.

We laughed because Paul was six-three, a rock climber, park ranger, and long-distance runner, and Frederik was five-eight tops, bald, with a slim, even fragile build, dressed head to toe in black. He gave the impression of either a retired cat burglar or a ballet dancer.

Sarah Cole, Anne’s and my childhood friend, and her boyfriend, Max Hughes, came over, hugs all around.

“Have you seen her yet?” Sarah asked.

“No, have you?”

“It’s totally mysterious. We’ve been here half an hour, and no sign yet.”

Loud voices echoed under the cathedral ceiling. Simple, pale wood furniture filled the room and rya rugs—contemporary, coarsely woven wool patterned with striking red and orange squares—covered the bleached pine floor.

Within a few minutes, Anne entered the room with Frederik. Her pale skin and dark hair looked striking against her long green velvet dress. He held her arm, led her to a group of Danes. They entered into earnest conversation, and I could tell my sister was resolutely keeping her focus on his friends to avoid making eye contact with us. Sarah walked over, stood by Anne’s elbow, but Anne pretended not to see her.

“Wow,” I said when Sarah came back without speaking to her.

“Bitchy the Great rides again,” Sarah said. We’d adopted the name from Hemingway’s Islands in the Stream. It was the nickname of a character’s mean girlfriend, and Sarah and I used it when Anne’s dark side took over.

I looked at my mother, who knew exactly what Sarah and I were talking about. She put her arms around our shoulders; she had become more confident and motherly since my father’s death. “She’s the hostess, and this is new to her. She’ll come over as soon as she can.”

“You’re right,” I said. “Can I get you something from the buffet, Mom?”

“We’ll all go,” she said.

Frederik’s delicate, eccentric glasswork filled an entire wall of thick, rough-hewn shelves; the contrast between gossamer glass and heavy planks made an austere statement. I saw small white dots on each glass piece and moved closer to see them marked with prices in both U.S. dollars and Danish kroner.

“It’s not very kingly,” Sarah said. “Pricing out the treasures.”

“It’s odd,” my mother agreed.

A large red-and-white Danish flag stretched across the wall above a sideboard laden with food and spirits: aebleskiver—ovals of fried dough topped with raspberry jam; boiled potatoes; roast pork; a basket of bread and plates of cookies.

The glogg—red wine mulled with nutmeg, cinnamon sticks, and slices of pear—bubbled in a large Crock-Pot. Several brown ceramic bottles of Bols Genever gin clustered behind a pyramid of clear glass mugs. Sarah and I ladled hot wine into mugs and passed them around.

A fire roared in the stone fireplace, throwing off so much heat the sliding porch door had to be opened. In the room’s center, a twelve-foot white spruce, decorated with iridescent ornaments, towered over the guests. Our group stood together, still waiting for Anne and Frederik to come over. We took plates of food, hung out with Sarah and Max, made conversation with a few people we’d met at the wedding, and waited some more.

The scent of spiced wine and gin filled the air, along with pine and smoke, and people milled about, many of the men smoking pipes and speaking Danish. One of their wives told us the party was intended to display and sell Frederik’s glass pieces: strange, abstract tubes of orange, scarlet, cerulean, and turquoise glass.

We read his artist statement posted by the shelves: From crashing spheres and the existential abyss I employ techniques born in the last century b.c. to merge the elements—air, water, earth, fire—refine them in my furnace, and blow the molten gob to create thinner and thinner layers, spun into “tunnels,” swirled with jewel tones, left open on either end, through which may pass spirits on their way to Himmel.

“Okay, I’m going to crack up,” I said. “‘Molten gob.’”

“You are an immature brat,” Sarah said. “Remind me again, what’s Himmel?”

“Danish heaven, weren’t you listening at their wedding?” I asked.

“Please, girls,” my mother said. “Be kind. Frederik is an extremely talented and accomplished glassblower.”

Why did that make us laugh? No good reason, relief of tension probably, plus the oddness of being in my sister’s home for the first time, seeing how she’d become instantly Danish, hurt because Frederik kept her talking to his friends instead of us. It stung when I glanced over, smiled at my brother-in-law as he accepted a check from a tweedy-looking man, and he did not smile back.

The food was delicious. Eventually Anne walked over with a tray of cheese, made a beeline for me. I was sure she’d say something sister-crazy about the madness of the party and how busy she was with the other guests and how she couldn’t wait to get to me, but instead she said, “Try the flatbread; it’s homemade.”

“By little elves?” I asked, joking along.

“No, by me,” she said, seeming honest-and-truly taken aback.

“Come on.” The Burke sisters had many talents; baking wasn’t one of them. I tried to laugh, but her expression was cold steel.

“Are you trying to ruin the party?” she asked.

“Hello, I’m your sister,” I said. “Balducci’s? Catering? I assumed—”

“That’s the trouble, Clare. You assume everything stays the same. My life has changed, and you’ll never get it.”

Huge metaphorical slap across the face—so sharp, my eyes stung. When we’d shared an apartment during college, we’d loved throwing parties but hated cooking, so we’d make secret runs to Balducci’s, miraculously located just a few blocks away. We’d arranged the prepared food on family china, thrown out the foil containers, and taken credit as if we’d cooked it all ourselves.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I know things are changing. You’re married, and—”

“Thank you. On that note, are you going to buy something?” she asked.

“Really?” I asked.

“Don’t you think his work is amazing?”

“Of course.”

“Frederik thinks you don’t like it.”

“I’m so sorry!” I said. “Why would he think that?”

“Because he suggested you look at it, and you haven’t said a word to him since.”

“Are you kidding? He’s ignoring us.”

“He has a lot of clients. Some came from Denmark just for this party.”

“Okay, that’s impressive,” I said. “But we’re you’re family, we love you, and—”

“And you know something else?” she interrupted. “He told me you made fun of his lineage.”

“Lineage? What are you talking about?”

“He has royal blood,” she said. “He said you were jealous and he’s right.”

“Of you being royal? Wow, let’s start over. We are not getting anything right tonight. Could you, like, snap out of it, and be my sister? I realize you’re in love, and Frederik is your husband, but I know you, all right? And you’re acting like an idiot.”

“How dare you speak to me that way in my home!” she said, backing away. Even before she could speak to our mother, who stood there waiting, Frederik called her over, whispered in her ear, and ushered her out of the room. She didn’t return for the rest of the night, and when we asked for her as we were leaving, Frederik said she had a headache.

I felt stunned, iced out by my big sister, alarmed by how not just mean—I could have handled that—but Stepford it all felt. She was under a spell. Was it possible Anne had met her male match? He was in complete control as he helped my mother into her coat and essentially pushed us out the door.

When Frederik called late that night, catching me just as Paul and I walked into our Chelsea apartment, he told me I had insulted his wife by claiming their party was catered and I would never again be welcome in their home.

He continued, saying I had demeaned his art and his family background, and that Anne wished to sever ties with me and wanted me to know that our relationship was over.

For a second I thought it had to be a joke. Ha, ha, I tried. But his voice was glacial as he repeated what he’d just said, and I turned livid. Here was a man I’d met a handful of times telling me how it was between Anne and me. Did he have any idea who we were, what we’d been through together, what we meant to each other? I was drunk on the mulled wine and my blood shot to the boiling point.

“Fuck you, asshole!” I told him to put Anne on the phone.

He hung up on me.

It took me years to understand that Frederik had laid down the law, and, even more horrifying, Anne had signed on to obey it. When I called her the next day, she yelled at me and hung up. That became a pattern. She declined every invitation, even from our mother, for dinner, holidays, mother-daughter days at the Met or MoMA, a walk across the Brooklyn Bridge.

After a while, the tide changed. We stopped pursuing her, and my mother and I began getting hang-ups. Sarah did, too. We’d answer and hear Anne breathing, but she wouldn’t say anything. “I know it’s you,” I’d say. Sometimes the silence would stretch on for a minute or two before she broke the connection.

Finally, after weeks of this, she called and we spoke.

“I’m pregnant,” she said.

“Oh, my god. Anne! I’m so happy for you. A baby!”

“I know. It’s blissful. We are over the moon.”

I wanted to ask why she’d been calling and hanging up, but forced myself not to. Our connection felt so tenuous, and the fragility in her voice scared me.

“A new baby in the family—oh, Anne. nothing could be more wonderful. How are you feeling? What’s it like?”

“I throw up constantly, but I’ve never been happier.”

“When are you due?”

A long silence. “We’re not giving out any details yet,” she said, her voice suddenly tight and stressed.

“Oh. Okay,” I said. I felt Frederik enter the conversation as surely as if he’d picked up the extension phone. “Whenever you’re ready, I want to hear everything. I can’t wait to be an aunt.”

“Aunty Clare,” she said.

I loved that. Her words warmed me, and I wished she were there in the room with me, so we could hug, celebrate, and plan, and she could tell me her dreams, like the color she hoped to paint the nursery.

“I have an idea,” I said. “Let’s have tea—the way we used to, with Mom and Sarah. We’ll go to the Met and look at Renoir’s paintings of mothers and children, to celebrate you and the baby—”

“You don’t even mention Frederik,” she said.

“Well, of course, Frederik, too. But I thought of tea as more of a girls’ thing. You know—mothers and sisters and aunts.”

“I don’t think getting together is a good idea. After the way you’ve treated him.”

“I’d treat him fine if I ever got the chance to see you.”

“He says you’re obsessed with our lives instead of your own.”

That stopped me cold. “Because I care about you? That’s so warped, Anne—why can’t you see it?”

“He said you’d deny it and turn it back on him. You so clearly have it in for him.”

Her voice caught on a sob, and she hung up on me. All I wanted was to call her back, start from scratch, figure out a way to keep her on the line. My hands were shaking, I couldn’t dial the number, but worst of all, I couldn’t figure out anything to say that would fix the icy distance between us. Because the issue, it had become clear, was Frederik.

I thought back to the very beginning of their time together. One week before their wedding, Paul and I had dinner with them in the back garden of Chelsea Commons, our favorite neighborhood haunt. We’d been so excited about meeting this guy Anne loved so much.

“How did you get into glassblowing?” Paul asked.

He chuckled. “That’s such a funny way to put it. I’m not sure one gets ‘into’ glassblowing.”

“Well, I meant, what sparked your initial interest?”

Frederik sipped wine and leaned into Anne, shoulders touching.

“It’s good of you to be so interested,” Frederik said. “I just don’t want to bore you.”

“Come on, I really want to know,” Paul said. “It’s art, but I’m also interested in the science. The way you work with sand and fire.”

“It’s very strange,” Frederik said. “A type of, how do I put it, spiritual madness? I literally have to do it.”

“I can understand that,” Paul said. “The way work becomes an obsession, when you really love the work to begin with.”

“Tell him, Frederik,” Anne said. “It’s so fascinating, the way—”

“There’s nothing fascinating,” Frederik said. “It’s hard to explain art.”

“Well, how about from the scientific perspective?” Paul asked. “The method you use, and the materials; what temperature do you have to reach in order to make glass?”

“I use a high heat, 1040 degrees Celsius,” Frederik said. He smiled and dropped the subject. Paul seemed not to notice, but my stomach flipped, feeling Frederik’s condescension, as if he thought speaking to an Urban Park Ranger was just an amusing waste of time.

I wanted to tell Frederik if he desired art, obsession, or spiritual madness, he should try Central Park. Paul is one of the great sky watchers. By night he guided star walks, taking people into the darkness of the park and watching the Perseid and Leonid meteor showers, the transits of Mars and Venus, phases of the moon, constellations bright enough to be seen through the city’s ambient light.

Some days Paul incorporated bird walks with “skying”—a term he’d picked up from a note by John Constable, the nineteenth-century British artist and possibly the greatest cloud painter ever to live. Paul could identify every cloud in the sky—cirrus, stratus, nimbus, cumulonimbus, nimbostratus, cumulus—feel the wind speed and direction, and predict the weather.

Paul knew every tree by its bark and leaves, every flower in the Shakespeare garden and the plays and lines in which they were referenced. We were in love, but we were also partners in nature and the city. How could Frederik think that was anything less than passionate obsession, gazing at the sky but with our feet on the earth we loved?

Anne had quit her job as a researcher in the NYU Biology Lab when she’d married him—giving her scientist boss three days’ notice.

“How can you just give up your work and screw your chances of any kind of recommendation?”

“Frederik wants to take care of me.”

“That’s a weird way to put it.”

“Why? I’ve always wanted that.”

“Love is one thing, but why do you need him to take care of you?”

“Because no one ever has.”

The words stung. Hadn’t we looked after each other our entire lives?

“Be happy for me,” she continued. “Frederik says we’re fremstillet I himlen. Made in heaven.”

“I am happy for you,” I said, and I meant it, but I already felt worried. Turns out, I had reason to be. Frederik’s heaven meant separating Anne from our family. He’d controlled her the best he could, and I’d never returned to their house until I showed up today.

Gilly, five, colored pictures for me as I held three-year-old Grit and read her Owl Moon, one of the books I’d brought. I wanted Anne to remember our own owl story, to remind her of how close we’d been. Grit clutched my hand, excited to find the hidden creatures in each illustration. I stroked my niece’s dark curly hair, thinking of how much it was like Anne’s when we were little.

We drew pictures. Trees, owls, clouds. I sketched the three cats, telling Grit and Gilly about each of them, how they liked to sleep on the bed just as if they were people, but how they stalked at night, chasing shadows and moonlight.

Through it all I kept watch on Anne. I saw bruises on her wrists and cheek.

“Did he do that?” I asked.

The kids were listening. She hesitated.

“Daddy hurts her,” Gilly piped up, throwing his arms around her neck.

“Come with me,” I said. “Pack some things, and let’s go.”

“Where would we stay? The three of us—”

“In the apartment, in your old room! Come on,” I said, driven by Gilly’s words and the fact that she hadn’t denied them. “Anne, we can figure out everything later. Let’s just leave.”

“Where are we going?” Gilly asked.

“To New York,” his mother said. “To your aunt’s house.”

She rose, stood looking around the room as if saying good-bye, or deciding what to take, or perfectly stunned by what she had just decided to do. Or maybe she had heard the front door lock click. Frederik stepped inside, a mild smile on his face.

“If I hadn’t come home for lunch, would you have left me?” he asked, shining that frightening half-smile on Anne.

“Daddy,” Gilly said.

“You’re not going anywhere,” Frederik said, knocking Gilly aside to grab Anne by the throat.

I slapped and scratched Frederik, tried to pry his hands from Anne’s neck. The kids screamed, and so did I. I reached into the fire and grabbed the charred end of the burning log. I swung it like a baseball bat, straight into his face. It smashed his cheekbone with a loud crack, and he let go of my sister. That’s all I cared about.

The cops don’t believe my version of what happened.

After being booked I called Paul and asked him to have my lawyer meet me. She never made it to the station house and hasn’t yet arrived here at the jail.

Now I’m in a cell. No window, no natural light, but there are brash greenish-white overhead fluorescent tubes over which I have no control. There’s a half sink/half toilet, stainless steel with no seat. Just the bare frame like the kind you see at arenas.

The cell is cinder block with a drain in the middle of the concrete floor, and a narrow bed attached to the wall. I’m alone.

They’re not granting me privacy out of kindness; they consider me dangerous to others and myself. It’s a fact, and I’m not denying it, that I bashed my sister’s husband in the face with that burning log.

I hear my sister choking, the children shrieking, and see myself dive at the fireplace and come out swinging. The smell of my burned flesh makes me throw up. Or maybe it’s the sensation in my wrists, bones reverberating with the violence, the impact of the log breaking Frederik’s nose.

I’m on suicide watch. When the sheriffs turned me over to the prison staff, a female guard strip-searched me. I looked at her nametag: Officer Fincher. She is tall, stocky, and muscular. She’s built like marble. I had expected depersonalization, but her eyes met mine. I saw a woman-to-woman flicker, almost as if she was sorry for me.

She told me to strip, and I did. Everything off—underwear included. My gauze-wrapped hands are like paddles, so she helped me unclasp my bra. Clothes went into a pile. Then she slipped on a pair of latex gloves and had me stand tall, spread my arms and legs.

“Open your mouth,” she said, and looked inside with a flashlight. She checked my ears, up my nose. She examined my armpits, navel, and the hair on my pubic bone.

“Hands on the wall, bend over,” she said, shining her light at my buttocks.

She gave me cotton underwear and an orange jumpsuit, a pair of sneakers with Velcro closures. No belt, no laces.

“Your lawyer coming?” Officer Fincher asked.

“My boyfriend called her,” I said.

“What’s her name?”

“Mary McLaughlin,” I said.

I know her,” Officer Fincher said. “I know most of the defense attorneys.” I waited for her to make a comment about Mary McLaughlin being smart, or good, one of the best, but by then our eye-to-eye, woman-to-woman moment had passed.

Finally Officer Fincher left, and I was alone.

I lay down on the bed and closed my eyes. I couldn’t stand looking at those scrubbed mint green walls terrorizing me with the idea I might be here forever. I kept hearing the panic and disbelief in Paul’s voice when I called him at our apartment. I wondered if I’d ever get to return to Chelsea, to Paul, our cats, our friends, and my work at the institute for Avian Studies.

I thought of Anne. She must have gone to the hospital with Frederik. I wondered how badly I had injured him—not because I care about him, but because I’m worried about my sister and what he’ll do to her and the children if he recovers. He doesn’t deserve her lying for him.

On my way into jail, I passed through two sets of locked metal doors. The sound of them clanging shut has lodged deep in my brain. Guards were stationed at desks behind bulletproof glass, with just a slit at the bottom, through which one sheriff’s deputy handed my papers. A radio was playing, and between the first set of doors I heard the sung phrase “We stole some clothes, but I wanted love; I know that my sister did too . . .” And by the time the sheriff’s deputies, one on each side of me and my heart skittering up my throat, rushed me through the second set of steel doors, my mind called up the next part of the song: “. . . Lilly Pulitzer gave up her ghosts; we wore pink, but inside we were blue . . .” I can’t be sure whether I actually heard that second phrase or only imagined it. But it didn’t matter because suddenly I was not only hearing “Crime Spree”—a song from long ago—but singing along with Anne, years before she’d met Frederik, one summer day in Central Park, lying on our blanket in the Sheep Meadow, tanning in bikinis and listening to WABC. We were fifteen and sixteen. Blue sky, sun, the park, being together.

The Sheep Meadow was packed with sunbathers, but we found a clear spot without too many little kids around, within easy sight of three Collegiate School boys we knew from the Gold and Silvers, the Christmas dance at the Plaza, who were playing Frisbee.

We sprayed Sun-in on strategic face-framing strands of our black-brown hair—blond was one dream that would never come true. My hair was long and straight, Anne’s short and wavy; I wanted hers, and she wanted mine.

Scorching heat filled the city like milk in a bowl—it rose up from the sidewalks, the pavement, and the park’s walkways, benches, dry grass, and lumpy boulders of New York gneiss and Manhattan schist.

“Crime Spree” came on, and we liked the song’s cockiness, the attitude: two sisters against the hard world, behaving badly in ways we would only sing about. They’d lost each other somehow, an idea unthinkable to us.

She kissed the lawyers on Folly Beach

I scammed on Azalea Square

Northern good girls on a southern crime spree

On the road with nothing to wear.

Sometimes the world is a crazy place,

It gives and it takes right away,

If I could trade everything just for a space

In her life, well I’d do that today.

We had to leave home but we didn’t know why

We each had a stone in our shoe

We spoke the same language no one else could hear

Big sister, you know I miss you.

Kids came around with black garbage bags full of ice and Heinekens, and Anne bought six beers for us.

We were underage, but she was my older sister, and no one cared anyway. We both liked to get numb. We lay on our stomachs, bikini tops untied to drive a group of Frisbee-playing Trinity School boys crazy, and she told me the tallest was named Park, and she kind of liked him.

Sitting in jail, I wished for “Crime Spree” to be a sign. I felt the spirits of our young selves fly down from the heaven where wisps of brave, radiant teenage girls go once their dull, inducted middle-aged replacements take over.

I had to believe that the ghosts of the young, wild Burke sisters had taken over the guards’ favorite radio station just long enough to blast twelve seconds of that song to give me strength and remind me of my sister: not the Anne now, but the Anne then. To remind me of why I’d done this for her.

I want the song and memory to drive away the knowledge that I’d completed Frederik’s job for him, convinced Anne to cut me from her and the children’s lives for good. The spider silk of today’s reconnection would break. We would become reestranged, only in a much worse way. The song is in my head, but so is a map of the future.

I tried to kill her husband. My lawyer will say I was defending my sister, but Frederik will convince Anne at least to pretend to see it his way. He will get her to deny my story and show the court my letters and e-mails, proof of my feelings about him. I will serve time in jail, no matter how good Mary McLaughlin—a friend of Sarah’s— might be. Anne will never visit or write to me. Her kids will grow up and I’ll never know them.

A man who fears and despises me will write my future.