1.

Oh little girl. You were the baby among the original three cats, and somehow, in a blink, you became an old kitty. It took you a long time to warm up to me--to anyone. You were made for the outdoors, for alleyways and forests--but I kept you inside. Your spirit couldn't be contained. You would gaze through the window at the rising sun. You would stare at the moon. You had an inner life. You had angry eyes and a twitching tail. The kittens arrived a year after Maggie and Mae Mae died, after you'd had a taste of being the only cat in the house. Although you were first wild with anger, you slowly let in Tim's love and it changed you. In time, you began to tolerate me and Emelina. By the end, I would say you actually loved us too, not just Tim.

That glamorous girl with the mean green eyes.

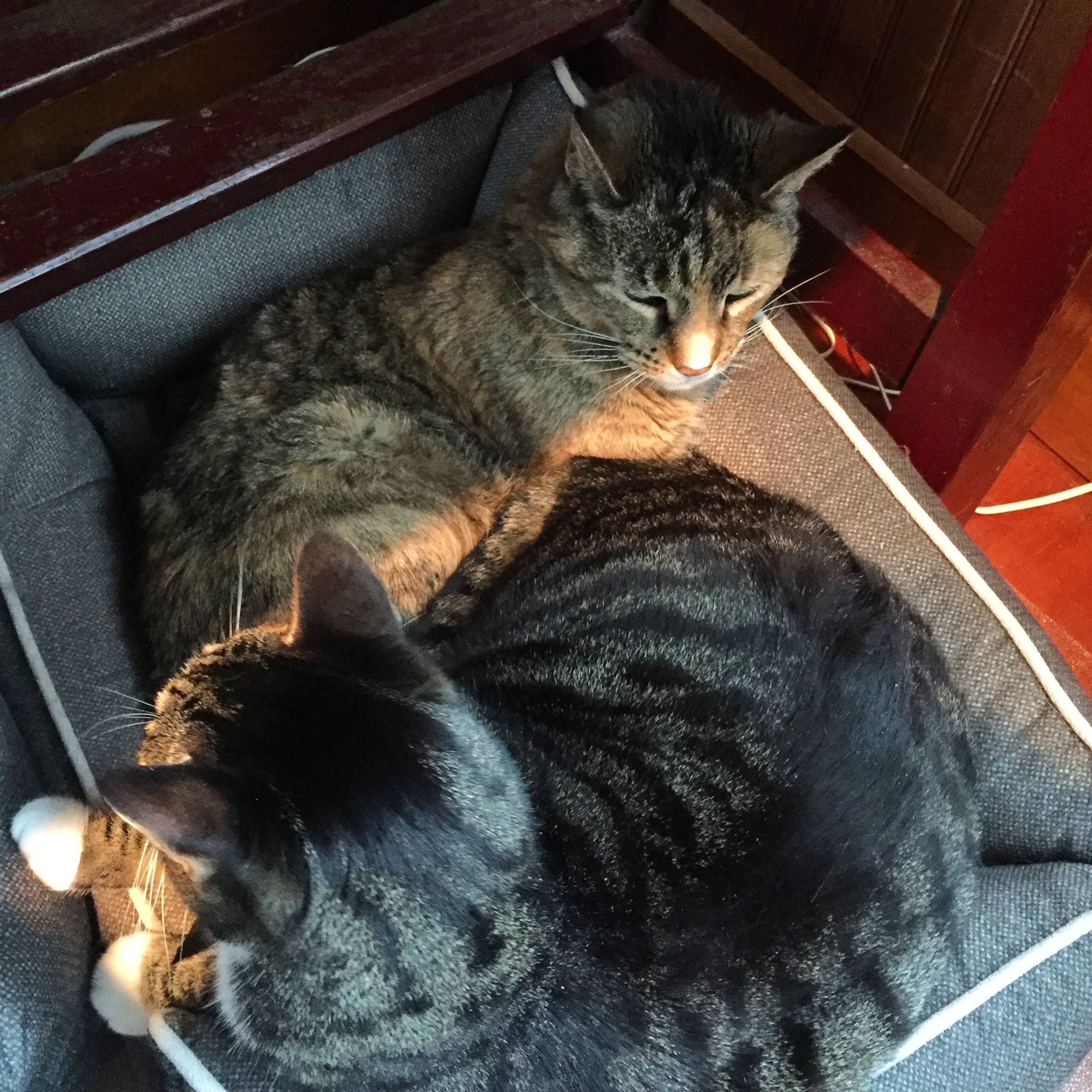

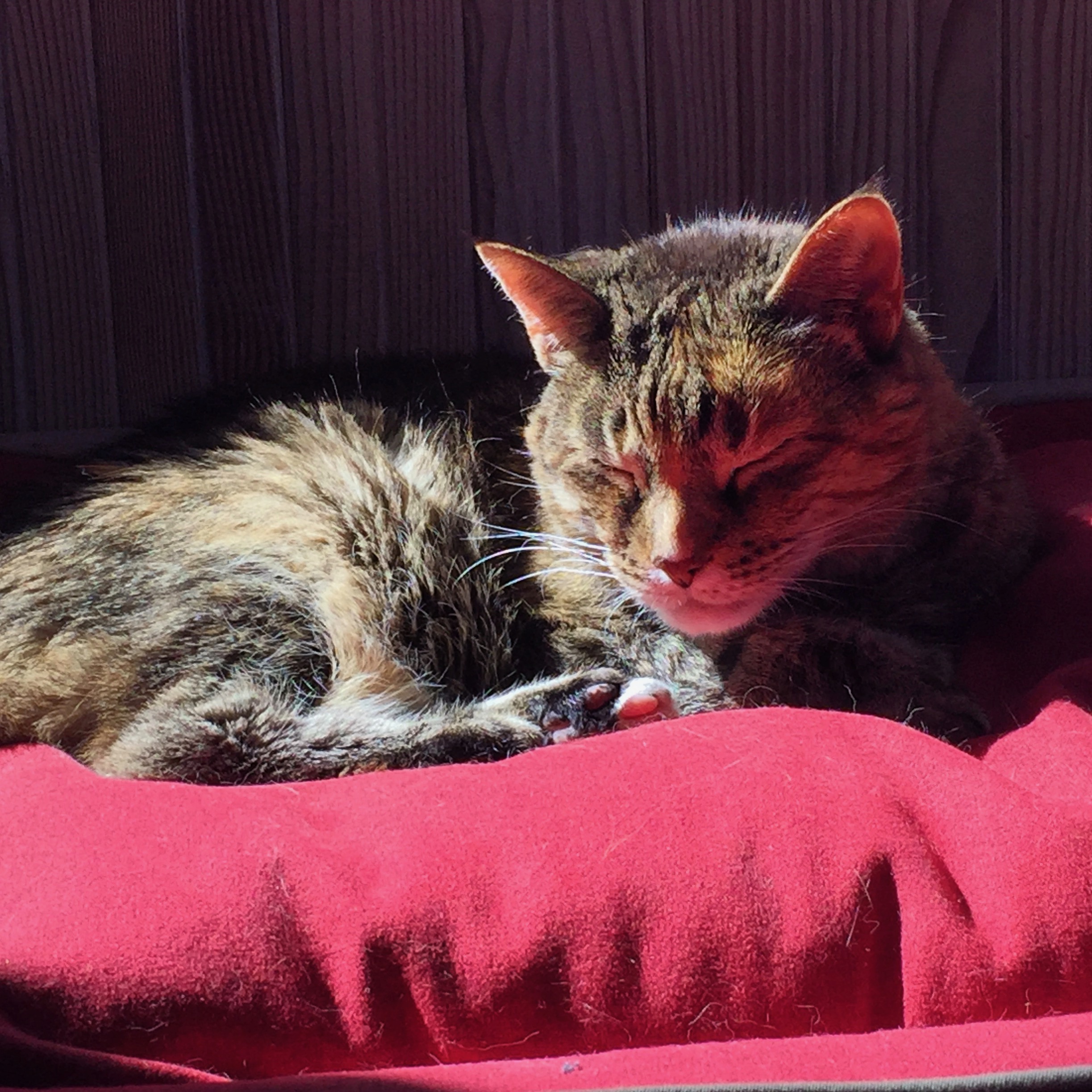

(Here are photos of Maisie, Tim, and Emelina--all three--together after...well, after Maisie softened toward the world. It took Tim to help her do that. The expression in her eyes became, mostly, less sharp):

2.

Love transforms.

(Maisie and Tim)

In the morning sun, under my desk.

Two nights before Maisie died.

3.

Cats are like humans while, at the same time, being nothing like humans or any other creature on this earth. They listen with their fur. They live for night, for the whisper of mice in the walls and bats in the trees. They see ghosts in the moonlight, and if you follow their gaze, you will see them too. Legend has it that cats are the familiars of witches, but that is only partly right. They belong, mainly, to the angels, both dark and light.

The way cats are like humans is how they need both solitude and connection. They can hide so completely--right there in your own house, every inch of which you know, in closets or the cellar or the attic or the chimney shelf or the back of your sweater drawer--and you will never find them. But when they are ready, they come twining around your legs, leaping onto the back of the chair where you sit reading, nudging your hand so you will pet the back of their heads, in the exact spot where their mother licked and cleaned them with her rough tongue when they were babies, to let you know they need reassurance of your love, oh they need it so badly.

4.

Maisie started out all cat, but during the last year of her life, she became at least partly human. I began to understand her. We started speaking the same language. This is how she told me that she was sick. The change was subtle. I might have missed it. We had mostly moved back to Hubbard's Point after mostly living in New York City and Malibu. This was the house she had come to as a kitten. Perhaps the ghosts that live here called to her. In response, I called a veterinarian who made house calls--Dr. Jennifer Hall. Something was wrong with Maisie, and Dr. Hall had to find out what it was.

She did find out--Maisie had a collection of illnesses that had been hiding for a long time. This was in September 2016. For months, through autumn and the cold winter and all of blessed green spring and into the summer, Dr. Hall came every week, like the veterinarians of dreams and literature. She tended to Maisie. Now, Maisie wanted to live--that was certain. She couldn't bear to leave Tim, and he wouldn't let her. But Dr. Hall is an angel, an angel of light who heals with a combination of science, medicine, intuition, and love, who ministers to the animals but also to their humans. Without her, Maisie would have died months ago. And you know what? Her last months were, perhaps, her best--when she relaxed into us, into being loved a little more, when she really learned how to purr. She hadn't before. She was a cat without a purr. Tim taught her.

Dr. Jennifer Hall, our wonderful veterinarian.

Dr. Hall and assistant Tammy. We are so thankful for all their care.

My ride's here.

4.

As the first day of summer approached, Maisie began to die. I saw her start to walk toward death. Her steps were slow but sure. Tired by her journey, she slept a lot. There were some nights she didn't jump up on the bed but instead found a dark place in a closet or under the desk I'd brought home from Paris. No matter where she hid, Tim would seek her out. He would lay against her side, pressed so close there was no chance of an inch of space between them. His warmth must have felt good. His presence kept her tethered to our house, to our lives and her own, kept her from drifting too quickly into the dream of death. Still, though, she kept walking in that direction.

5.

In June I started taking Maisie outside. She was too weak to run so I knew she wouldn't disappear through the lattice under our neighbor's cottage or up the old and spreading red oak tree. I knew she wouldn't chase the 20 or so bunnies that live in the lily patch and under the rock ledges. There was no way she could kill the birds--I counted six species at the same time--that darted through the branches and oak leaves above us, squawking and crying that a cat, a predator, was out and no one was safe. Except they were, because Maisie moved so slowly.

6.

I planted a garden. This yard had been badly neglected during our years away. I thought of the garden as life. I wanted the snapdragons, larkspur, clematis, bee balm, cosmos, delphinium, sweet peas, shasta daisies, coreopsis, and zinnias to bloom and bloom, as if all that beautiful life could chase and vanquish Maisie's death, because I felt it coming. I placed a teak bench beside the privet hedge, and while bees buzzed behind our heads, Maisie and I would sit there in the summer evening while I fed her shrimp by hand.

7.

There were days when she seemed to rally. I'd get my hopes up. This wasn't cat hospice after all--Maisie's health was going to improve in a real and substantial way. She was only sixteen. To some people that might sound old, but I've heard of cats who live to twenty, twenty-one, twenty-five. One friend had a cat who lived to be twenty-nine, and every day he fished off a dock that jutted into the Connecticut River at Brockway Ferry in Lyme, catching shad with his right paw, eating the fish--even though he'd lost most of his teeth--and spitting out the bones. Then he would go into the house, up the creaky stairs, into the back bedroom closet, pee on the shoes, and fall asleep.

So sixteen seemed very young to me and I hoped and honestly believed that Maisie would get better. These hopes were not just for me. They were for Maisie, Tim, and Emelina. We are a family, after all. But the rallies were small, and they fizzled out, and each time Maisie would be a little older and more tired, a little more ragged. Dr. Hall began to call her Grizabella, and so did I.

8.

You see, I had this plan. In Laurie Anderson's Heart of a Dog she talks about how, when their terrier Lolabelle was very sick and they knew she wouldn't get well, Laurie and her husband Lou Reed brought her home from the hospital. There would be no putting her to sleep. Lolabelle would be comfortable, and she was, and she would have the dignity and process of her own death, without anyone taking it away from her. I love Laurie, and that way of treating Lolabelle felt right to me. Here are the notes I made when I made the decision not to put Maisie to sleep, but to let her go in her own time:

When Dr. Hall was here, I apologized and apologized, feeling bad for having her come here on both Saturday and Sunday. We both cried, and she said don’t be sorry.

Maisie not eating, drinking just a little—but sitting up, walking upstairs, now sitting in her bed beneath my desk.

Dr. Hall said if this was CATS, Maisie would be Grizabella and Tim would be a stagehand.

People expect you to put an old/sick cat to sleep.

Friends ask, expecting me to have made that decision.

I don’t want her to suffer—but she’s not suffering. She is peaceful. She now purrs when I scratch under her chin and the top of her head.

This morning Tim nuzzled her the whole way into the kitchen.

Am I letting her tell me what she “wants?” She is still comfortable and enjoying small things in life. This morning I opened the screen door and she walked outside.

But she is listless, sometimes goes into the dark closet upstairs in the bunkroom, isn’t eating (just a few bits of fluke I cooked for her,) is drinking less and less—only a few laps from her water bowls. (Three, and I keep them all filled to the top with fresh water, the way she likes it.)

9.

After everything, Maisie died yesterday. In spite of my plans, my well-thought out plans that would let Maisie just fall asleep on her own, I saw a big change in her, saw her cringing, her hind legs going out from under here, and at 7: 30 a.m., within minutes of noticing, I texted Dr. Hall. While we waited for her to come, Tim did what he always did: tended to Maisie. He kissed her while she tried to drink water. He loved and comforted her, and, probably himself. What will he do without her? The one thing I knew was that we couldn't let Maisie suffer in her body. Tim, Emelina, and I sat on the bed while Dr. Hall gave Maisie the shot.

10.

After Maisie died and her body left the house, Tim stayed on the bed. He kept trying to burrow under the blanket she'd always slept on, looking for her.

11.

When it was time for dinner, I called out, "Are you hungry?" That question had always summoned the kitties from wherever they were. Tim, every single time, had accompanied Maisie down the hallway to the kitchen. He'd press against her, leading her toward food, sometimes tripping her, he walked so closely. Last night he ran around the house, searching for her. Of course she wasn't here. He ran and ran. He looked everywhere. I had to wait for this to end, I couldn't rush him. He had to discover for himself.

After a while, after he had worn himself out, I asked more quietly, "are you hungry?" and both he and Emelina came into the kitchen. Patrick had sent us flowers of sympathy, and the kittens (forever the kittens, no matter how old they are) had to inspect.

Maisie is in the bardo. Laurie Anderson says that the one thing the Tibetan Book of the Dead prohibits is crying. Crying will encourage the dead to stay here, in this realm, with us, but they can't stay. They have to leave.

But, see, I cried: I cried before Maisie died, while she was dying, and when she had stopped breathing and I held her body.

Last night, after Tim finished his search, he and Emelina walked to their bowls. They began to eat. Perhaps by crying I had caused Maisie--not her body, but her ghost--to stay. I'm pretty sure the kittens felt, as I did, Maisie's spirit in the kitchen.

Just out of the corners of our eyes, her tail was twitching. I saw it last night. I don't see it today. Maybe Tim and Emelina do. I hope Tim does.